Individualized, Inclusive, Innovative: AMPed Hybrid Academy in Metro Detroit Michigan

Anne Marie Palazzolo knew she wanted to be a teacher when she was five years old. After pursuing a degree in Special Education and Emotional...

3 min read

Don Soifer

:

Jan 12, 2023 11:38:27 AM

Don Soifer

:

Jan 12, 2023 11:38:27 AM

.jpg)

Neurodiverse children, and others whose learning is impacted by diverse levels of ability, are thriving in microschools in ways many never did in their traditional or even public charter schools.

How can this be, public education devotees react? Public dollars and federal special education help, after all, don’t generally follow a child who opts out of public schools.

Yet, the reality is that many of them do find themselves in settings they find more advantageous to their growth and in learning in the diversity of innovative, small learning environments the microschooling movement embraces.

“In our microschooling community we have the opportunity to truly have a one-on-one conversation with the learner, their parents, and other providers in that learner's life to develop an individualized education program that works for that child, specific to that child,” describes microschool founder Anita Williams, whose background is as a practicing licensed therapist. “Sometimes this looks very unconventional, non traditional, and definitely outside the box.”

Accomplished, life-changing educators who prioritize understanding relationships, the smaller, often more personal settings they create in which to work, and crucial flexibilities to design and evolve their models around the specific needs of the individual learners they serve are all critically important factors.

Frequently families are leaving what they find to be a confrontational, compliance-driven public special education system on which public schools must rely. This still-deeply-flawed, and nearly always under-resourced amalgamation of hundreds of pages of statute and regulations has led to plenty of good historically, to be certain. But along the way, adhering to its process-heavy dictates, prone to being distorted by misinterpretation, lack of budget resources or simple convenience at the school building level, is often not what works best for everybody.

Today’s federal legislation offering protections for learners with special needs was last updated nearly twenty years ago. Amid a broad acknowledgement at the time by lawmakers, educators and advocates alike that the process produced some improvements, a consensus at the time admitted that compromises of the deliberative process had yielded a still-broadly-imperfect set of remedies.

These protections center around an Individualized Education Program (IEP) process, which can easily become a highly confrontational one, driven by a decisionmaking team for each child required to include, but not necessarily side with, parents.

Microschool founder and veteran educator Amy Novak notes that within IEP team meetings, parents have input, but their priorities often lose out to staff recommendations as, “there is a hierarchy in these meetings that often do not have the child's passion or life purpose integrated.”

Making matters worse, IEP teams’ lengthy, compliance-driven reports of recommendations are often not read for understanding by otherwise hardworking classroom teachers, and even when recommendations are followed with integrity by schools, they may represent only certain aspects of what will help children approach their potential, and even then not to a degree parents or experts deem sufficient or "appropriate" as the law's protections ostensibly require.

What’s more, as microschool leader Williams observes, “So often the IEPs in our current educational system are a ‘one size fits all’, and are often copied and pasted from IEP to IEP (having nothing really to do with the child that the IEP was about)....” This can lead to recommendations which, even when backed by sufficient resources and staffing, often do not translate to classroom experiences where children with neurodiverse or other diagnosed conditions will thrive.

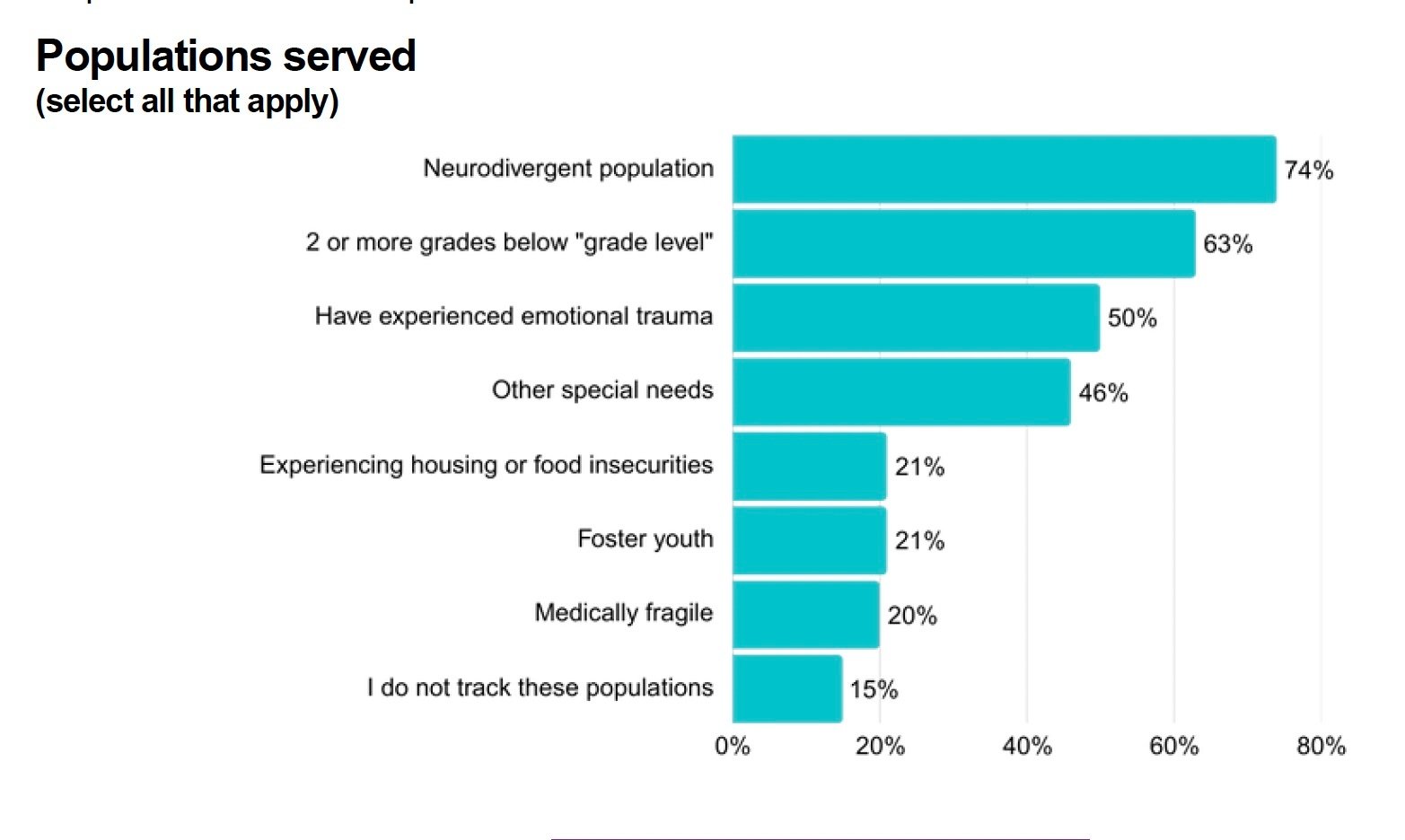

Which is a major reason why so many microschool founders and leaders describe receiving strong interest from families of learners with special needs, and especially neurodiverse children, in microschooling.

Family-Friendly Solutions

School choice programs in some states, like West Virginia, Florida and Arizona, permit families to use public dollars to access microschools and other nonpublic options. For decisionmakers in these and other states, it will be important to establish seamless mechanisms for families to access microschooling models which are often newer than existing regulatory frameworks, which in turn did not fully anticipate their small size or innovative, flexible models.

Both federal and state decisionmakers have an important opportunity to strengthen parental rights by giving families more choices to ensure that their children have access to the free and appropriate education to which they are entitled. These can include sensible measures like allowing microschool operators and other nonpublic schools to access Medicaid reimbursements, something only two states currently allow. Indeed, opportunities for parents to choose nonpublic settings to apply the public resources to which federal law entitles them are quite limited in practice in most jurisdictions.

Nevada’s family-friendly TOTS grant program offers families of special needs learners grants of $5,000 which can be broadly accessed for various educational expenses, including microschooling.

Policies like these can go a long way toward expanding equitable access to microschooling options which have proven quite popular with families of learners with special needs.

Notes Nevada microschool leader Novak, “When children are in a learning environment that allows individualization, integration happens naturally with typical peers and then progress can be observed. Our world reflects diversity, but for some reason children with special needs are not allowed to sit with the others. What does that mean for ALL children?”

-1.jpg)

Anne Marie Palazzolo knew she wanted to be a teacher when she was five years old. After pursuing a degree in Special Education and Emotional...

My name is Alexandra Batista I am the founder of Steps Learning Center LLC, born and raised in Puerto Rico. I graduated with a double Bachelors...

Today’s highly diversified microschooling movement can be seen growing and evolving in response to educational needs and interests within the...